1897 and Erdmann the German

The German foray in Africa is known for its genocide of the Herero and Nama peoples in Germany’s attempt to erase them from the face of the earth. On our West African coastline however, accounts of Germans are scant, as we all know, though not so scant as we may believe, especially as some of the surviving and earliest European accounts appear to have been written by German visitors and/or traders on the West African coastline. It would seem that on our coastline the German foray is largely, how shall we say, 'harmless'? Amongst these early German travellers to West Africa however there is certain ‘Groeben’, sent in 1682 by his king to the Sierra Leone and Sassandra Rivers, whose 'account' is more concerned with depicting Africans in caricatures. But that is just out of others of far better insight whose accounts of West Africa are remarkably contemporaneous with the nature of travel, even cosmopolitian and urbane in tone. In any case, for a nation of people whom Amilcar Cabral describes as “the most tragic expression of imperialism and of its thirst for domination”, the incursions of Germans into West African history is almost always interesting. An example is the barber-surgeon, Ulsheimer, working on the Dutch Guinea Company ship, who arrived closer to our side of the coastline and not only assisted, in 1603, the Oba of Benin in 'subjugating a rebellious settlement' in present day Lagos, he even went, on the invitation of the old king (Oba Ohengbuda), with the king's entourage and visited the ancient city itself, Benin City. To date, Ulsheimer is the earliest record we have of any mention of a settlement on the lagoon, which it states as a protectorate of the Benin kingdom. Forward to the relatively 'recent' era of the stolen Benin Bronzes and artefacts and we have the already well known part played by Felix von Luschan whose role served to lead the Brits in having second thoughts on their vapid, perfunctory sale of the looted arts stolen from the palace in Benin City. On that week in February, 1897, after the murders of people and burning carried out by the British on the ancient city Benin City -- (PS: the burning and looting of Benin City by the English involved the mass murders of citizens of the city which is hardly if at all mentioned in the many propaganda published right afterwards by the English) -- the invading British troops, eager for bounty, were hugely disappointed to find not gold but brass and bronzes and wood and clay: terra cotta. Their greed was only appeased in finding thousands of carvings in ivory -- carvings which would have been made not by the more established ancient guilds such as Igun Eronmwon but by the palace pages, omada (carriers of ada), as ivory, considered easier to carve, was their designated medium. The British troops were thoroughly disappointed at not finding gold and promptly resolved to sell off the loot as quickly as could. To their mind, they'd be lucky to find some reasonable quid for the loot and would likely have to hoard the rest someplace until even those can be disposed of. Within a couple of years, thousands** of sacred Benin arts and Benin bronzes, stolen from the palace in Benin City in 1897, were summarily sold off or damaged from indifferent storage and lack of real appreciation. The utilitarian-minded British have never been great appreciators of Art, in any case. It was the German Felix von Luschan, the then assistant director of the African section at the Museum für Völkerkunde who, noting at the time that 'these are works equal to the very finest examples of European casting technique’ interrupted British commonness of mind and swiftly began to purchase as many as he could find of the looted artefacts for his employer, the museum in Berlin. It is ironic that today, ever since Oba Akenzua II made the first official REQUEST FOR RETURN OF THE LOOTED ART AND SACRED Objects, the very same looted artefacts the British Museum refused then and continue to refuse to return were, for the British and their queen, ever eager to find African gold as 'free' bounty, a thorough disappointment in not being made exactly of gold. The person in whom we are interested however is a certain 'Mr Erdmann' a man of no first name apparently, who was said to have been "a trader living in Lagos in 1897". On the day of the destruction of Benin City, Mr Erdmann must have hurriedly packed his camera and headed off to Benin City to take 'as many photographs' as he possibly could. We know this because fellow trader at the time, the British R.E. Dennett, mentions in one of his books that Mr Erdmann had told him specifically that he had taken "many photographs" of the palace right after its roofs were entirely blown off.

Unfortunately, as Dennett tells us, Erdmann died on his way back to Europe shortly after in 1904; it would seem that in all the time between 1897 and 1903, Erdmann never shared his photographs with his buddy, Dennett.

So many questions about this strange fellow, Mr Erdmann. What business exactly was he doing in Lagos in 1897 and for whom was he working? How long was he in Benin City for? How many photographs did he take of the city on that day of destruction or the days after and, since, according to him, they were in fact "many", where are they all now?

Well, we'll have to ask Germany a country whose presence though seemingly scant in West Africa is on the matter of the Benin Bronzes, curiously heavy.

It is well known that the widow of Mr Erdmann handed over photographs to the same von Luschan of the museum in Berlin, though how many is not clear. What in particular did the widow of Mr Erdmann hand over to von Luschan? Is there an archive of it all somewhere in Berlin?

If it is difficult to find out anything about 'German trader based in Lagos Mr Erdmann' it is impossible to find out anything about his widow.

Luckily, the museum in Berlin is still in existence. The ancestral royal palace in Benin City from which the objects and sacred arts were stolen is very much in existence, as is the Benin kingdom — in an ever deepening sense of meaning and relevance to the nation of Edo Benin people.

It is our hope that, on this very important matter of the return of the Edo Benin people’s sacred arts and ancestral objects, the German nation will work diligently with the Edo nation, the Benin Kingdom, as represented by the Oba of Benin.

/

|

SOURCE: R E Dennett speaking in his book of Mr Erdmann |

|

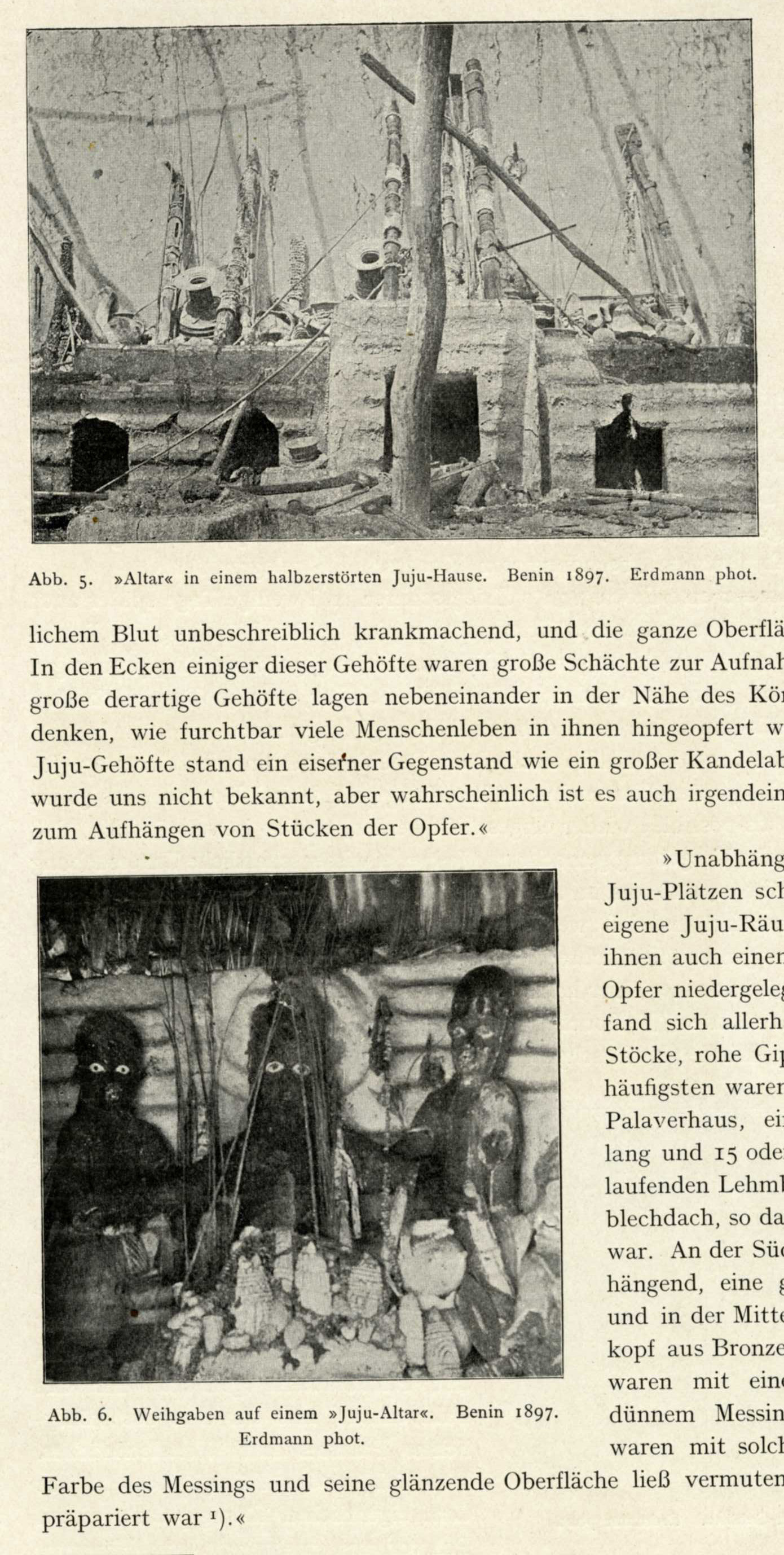

SOURCE: 1919. Luschan, Felix von. Die Altertümer von Benin; Photographer: Erdmann. 1897, BENIN CITY |

|

SOURCE: 1919. Luschan, Felix von. Die Altertümer von Benin; Photographer: Erdmann. 1897, BENIN CITY |

|

SOURCE: 1919. Luschan, Felix von. Die Altertümer von Benin; Photographer: Erdmann. 1897, BENIN CITY |

PS: TEXT ACCOMPANYING THE ERDMANN PHOTOGRAPH: Though Erdmann did not ‘see and candelabra’ ie of actual humans being sacrificed as taught him by propaganda, he however expected and imagined that what he saw, the ‘large shafts’ and ‘iron objects’ were in fact the imagined large candelabra of his mind. Benin Kingdom was not free of sacrifice, in fact the sacrifice of animals on altars to the ancestors was quite the norm. Benin Kingdom carried out capital punishments for serious crimes.

Translation from the incomplete German text: “Fig. 5. “Altar” in a half-destroyed Juju house. Benin 1897. Erdmann photo. ….” “In the corners of some of these farmsteads there were large shafts for receiving large such farms lay next to each other near the king. Think of how terribly many human lives were sacrificed in them. Juju farmsteads stood an iron object like a large one We didn't know of any candelabra, but it's probably one for hanging up pieces of the victims.<<

Comments

Post a Comment